Injectable Oxygen set to make resuscitation easier and safer...

AED Drone bringing help to the scene before ambulance arrival...

Why We Should No Longer Terminate Resuscitations after 20 Minutes...<click here>

Research shows defibrillation depicted in movies is far from accurate <click here>

The truth is out there...

While it is recognised around the world that the most common cardiac arrest is the Sudden Cardiac Arrest (SCA)...here in Australia we act as if the the most common arrest is in an adult who drowns while eating a meat pie. Very Australian but just not true!? See our discussion page and check out the facts.

Dr Heimlich saves choking woman with man-oeuvre he invented

The 96-year-old American inventor of the Heimlich manoeuvre has used the technique himself to save a choking woman at his retirement home. Dr Henry Heimlich said he had demonstrated the technique many times but never used it in an emergency. His action dislodged a piece of meat with a bone in it from the 87-year-old woman's airway. "I didn't know I really could do it until the other day," he told the BBC. Dr Heimlich was having dinner with eight or nine others at the Deupree House retirement home in Cincinnati when he turned to talk to a woman at his table and noticed she was choking. "She had a skin colour that was no longer pink. Her mouth was puffed up and her lips were out," he told the BBC. "Though I invented the Heimlich manoeuvre I had never been called on to do it before." Dr Heimlich described how he turned the woman, Patty Ris, around in her chair so her back was exposed. The manoeuvre requires a rescuer to carry out abdominal thrusts on a choke victim to dislodge the blockage. "I did it three times and a piece of meat with a bone in it came flying out of her mouth and she was all right," he said. Staff had rushed to the table when the woman started choking, but stood back to allow Dr Heimlich to carry out his manoeuvre. "Just the fact that a 96-year-old man could perform that, is impressive," his son Phil Heimlich told the Cincinnati Inquirer. Dr Heimlich, who invented the technique in 1974, swims and exercises regularly. He often meets people who were saved by the technique or who saved someone else, his son said.

Who has the Heimlich manoeuvre saved? Since the technique was introduced in 1974 it is believed to have saved the lives of more than 100,000 people in the US alone. They include former President Ronald Reagan, pop star Cher, former New York mayor Edward Koch and Hollywood actors Elizabeth Taylor, Goldie Hawn, Walter Matthau, Carrie Fisher, Jack Lemmon and Marlene Dietrich. In 2014 actor Clint Eastwood was credited with saving the life of a golf tournament director in California who was choking on a piece of cheese. In the UK, celebrity promoter Simon Cowell was reportedly saved by comedian David Walliams, who carried out the Heimlich manoeuvre on him after a mint became stuck in his throat.

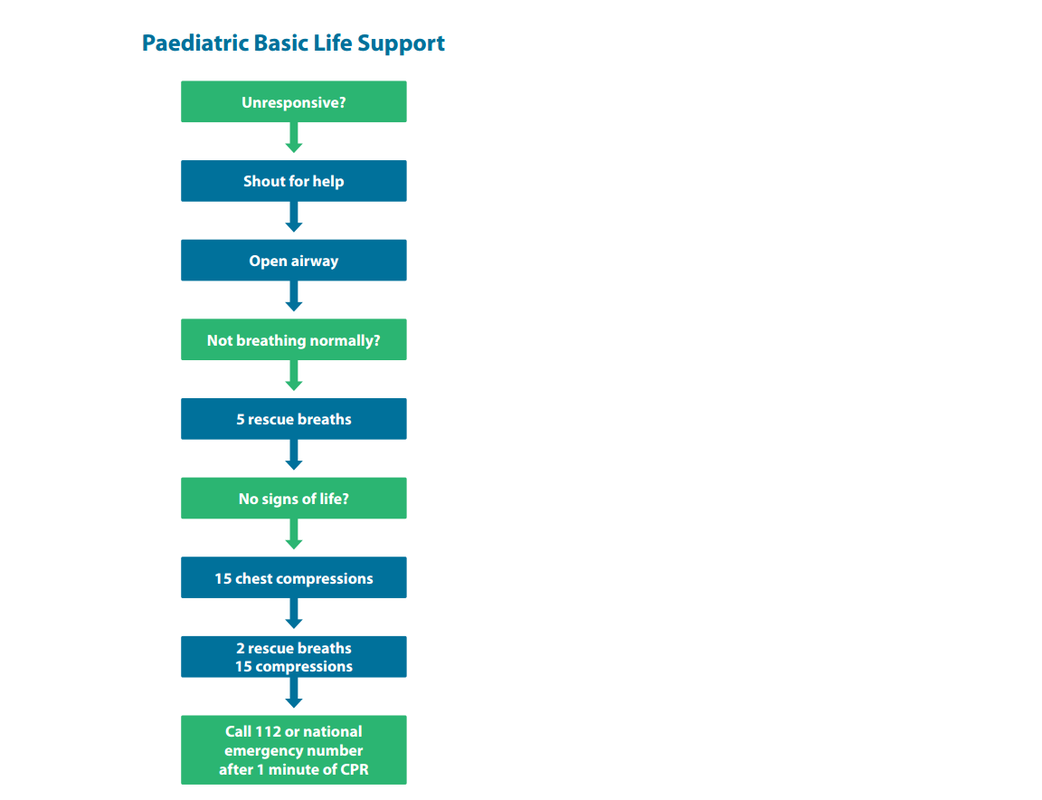

European Resuscitation Council releases new guidelines

The European Resuscitation Council (ERC) has released their new guidelines, including now recommending that the BLS Guidelines for Children be the same as the ALS Guidelines (see below). This includes using the ratio of 15:2 for CPR due to the high likelihood that a peadiatric arrest will by caused by a hypoxic episode.

The European Resuscitation Council (ERC) has released their new guidelines, including now recommending that the BLS Guidelines for Children be the same as the ALS Guidelines (see below). This includes using the ratio of 15:2 for CPR due to the high likelihood that a peadiatric arrest will by caused by a hypoxic episode.

ECC and AHA recommend first-aiders and other BLS providers are given Naloxone (Narcan) for narcotic over-doses

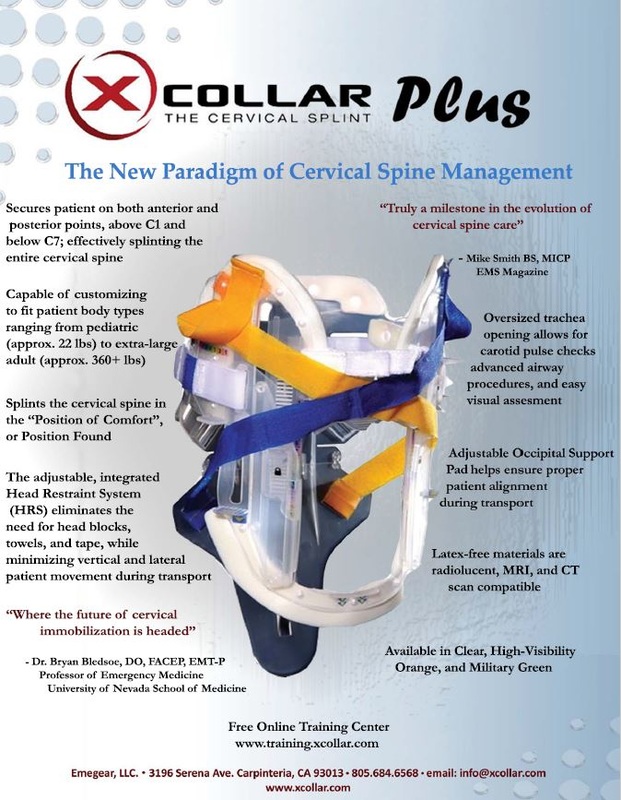

New Collars solves the issues for the critics of hard collars

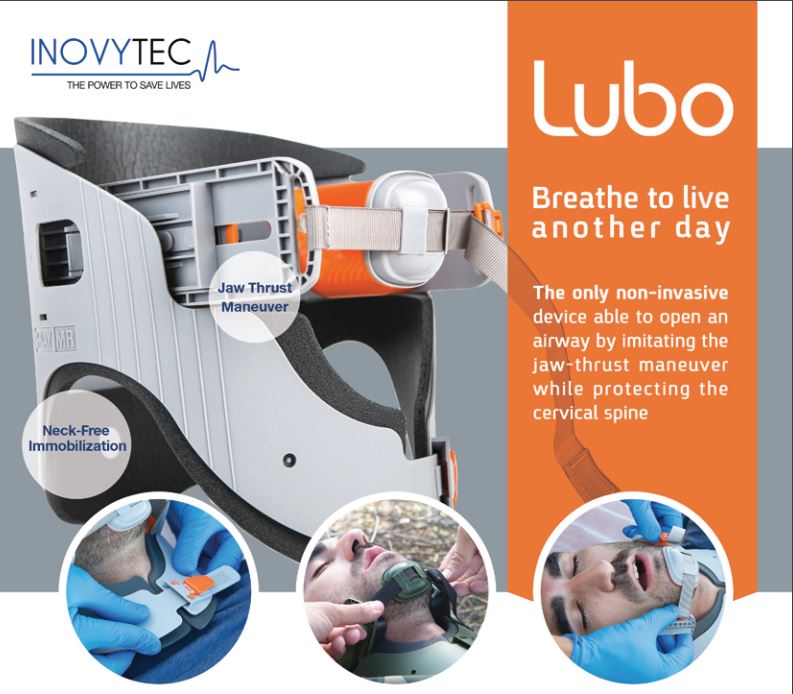

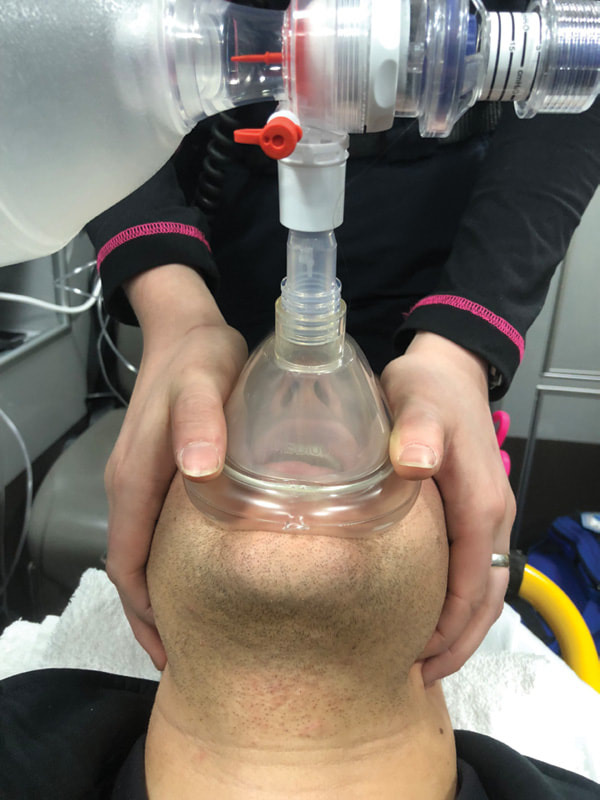

The Lubo

The Lubo offers a combined solution for both airway and immobilization needs. While the Lubo is the only non-invasive solution that can safely open the airway by imitating the jaw thrust maneuver for a long time, it is the only immobilization device that allows the care giver to manage the airway easily, frees the neck from the “traditional neck grasp” while performing solid immobilization.

Any first responder, paramedic or non-paramedic, learns in the Basic Life Support course to perform the Jaw-thrust maneuver using both hands.

On the one hand, this is a difficult technique that requires training in order to be performed successfully, and still may risk the patient’s cervical spine if done manually without preliminary immobilization. On the other hand, the common cervical collars may compromise the patient’s airway by obstructing both the professional medical personnel from performing intubation and the Basic Life Support first responders from manually performing a Jaw-thrust maneuver.

The Lubo offers a combined solution for both airway and immobilization needs. While the Lubo is the only non-invasive solution that can safely open the airway by imitating the jaw thrust maneuver for a long time, it is the only immobilization device that allows the care giver to manage the airway easily, frees the neck from the “traditional neck grasp” while performing solid immobilization.

Any first responder, paramedic or non-paramedic, learns in the Basic Life Support course to perform the Jaw-thrust maneuver using both hands.

On the one hand, this is a difficult technique that requires training in order to be performed successfully, and still may risk the patient’s cervical spine if done manually without preliminary immobilization. On the other hand, the common cervical collars may compromise the patient’s airway by obstructing both the professional medical personnel from performing intubation and the Basic Life Support first responders from manually performing a Jaw-thrust maneuver.

Lubo secures patent airway while immobilizing the spine without causing damage to the patient’s neck. Lubo also enables performing intubation, if needed, while maintaining cervical spine fixation.

Lubo meets the first-aid international guidelines, both civilian and military, allowing basic patent airway and can quickly be applied by any first responder. The Lubo can easily be included in any first-aid kit and therefore improve health and wellness in the community.

Lubo sales commenced worldwide through distributors specialized in out-of-hospital emergencies both to the civil (private and government) and military markets.

History

The Lubo stems from field experience in the Israeli Army (IDF). The inventor, Dr. Omri Lubovski, is a veteran in the prestige aviation rescue 669 unit. He realized that the need for opening the airway non-invasively, quickly and efficiently, is crucial especially when the victim’s situation or scene surroundings are complicated. The lack of ability to open and secure the patient’s airway while performing immobilization, led to the invention of Lubo.

The Need

The Lubo concept has grown out of two major needs in the field of emergency medicine:

This novel device is intended to enable non-invasive airway management in cases of trauma that require immediate airway management combined with an immobilization capability1.

Lubo’s main features

Lubo Family Models:

The Lubo family includes various models addressing the need to open and secure patent airway by any first responder in different segments of the critical care market, such as emergency services, first-aid kits, hospital ER/ICU, military and MCI.

Lubo Regular

Enables patented airway opening with cervical spine immobilization, adjustable to adult sizes, single-use for pre-hospital medical emergency care.

Lubo Military Model

Enables patented airway opening with cervical spine immobilization, adjustable to adult sizes for use by military forces. Robust, dark colors, for pre-hospital use, complied with TCCC and TEMP guidelines.

Lubo Mini

Enables patented airway opening with cervical spine immobilization, adjustable to small sizes, single-use for pre-hospital medical emergency care.

References:

Lubo meets the first-aid international guidelines, both civilian and military, allowing basic patent airway and can quickly be applied by any first responder. The Lubo can easily be included in any first-aid kit and therefore improve health and wellness in the community.

Lubo sales commenced worldwide through distributors specialized in out-of-hospital emergencies both to the civil (private and government) and military markets.

History

The Lubo stems from field experience in the Israeli Army (IDF). The inventor, Dr. Omri Lubovski, is a veteran in the prestige aviation rescue 669 unit. He realized that the need for opening the airway non-invasively, quickly and efficiently, is crucial especially when the victim’s situation or scene surroundings are complicated. The lack of ability to open and secure the patient’s airway while performing immobilization, led to the invention of Lubo.

The Need

The Lubo concept has grown out of two major needs in the field of emergency medicine:

- Non-invasive airway solution

- Cervical collars pitfalls

This novel device is intended to enable non-invasive airway management in cases of trauma that require immediate airway management combined with an immobilization capability1.

Lubo’s main features

- Non-invasive airway management.

- Imitates the jaw thrust maneuver while protecting the cervical spine. Performs a safer jaw thrust maneuver without risking the spine6.

- Avoids using ‘invasive’ airway devices OPAs (which can result in pallet trauma, nausea, vomiting and bronco-aspiration) and NPAs (which may lead to bleeding).

- Facilitates airway clearance (teeth, secretions etc.).

- Immobilization without compromising the airway and without grasping the neck.

- The only cervical collar that enables intubation (no need to remove the collar) and its immobilization is at least as good as the standard cervical collars.

- Easy to operate by any first-responders.

- Effective, fast and painless.

Lubo Family Models:

The Lubo family includes various models addressing the need to open and secure patent airway by any first responder in different segments of the critical care market, such as emergency services, first-aid kits, hospital ER/ICU, military and MCI.

Lubo Regular

Enables patented airway opening with cervical spine immobilization, adjustable to adult sizes, single-use for pre-hospital medical emergency care.

Lubo Military Model

Enables patented airway opening with cervical spine immobilization, adjustable to adult sizes for use by military forces. Robust, dark colors, for pre-hospital use, complied with TCCC and TEMP guidelines.

Lubo Mini

Enables patented airway opening with cervical spine immobilization, adjustable to small sizes, single-use for pre-hospital medical emergency care.

References:

- Lubovsky, O., Liebergall, M., Weissman, C. & Yuval, M. A new external upper airway opening device combined with a cervical collar. Resuscitation 81, 817–821 (2010).

- Lairet, J. R. et al. Prehospital interventions performed in a combat zone. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 73, S38–S42 (2012).

- Eastridge, B. J. et al. Death on the battlefield (2001–2011). J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 73, S431–S437 (2012).

- Uzun, L. et al. Effectiveness of the jaw-thrust maneuver in opening the airway: A flexible fiberoptic endoscopic study. ORL 67, 39–44 (2005).

- Durga, V. K., Millns, J. P. & Smith, J. E. Manoeuvres used to clear the airway during fibreoptic intubation. Br. J. Anaesth. 87, 207–211 (2001).

- Aprahamian, C. et al. Experimental Cervical Spine Injury Model : Evaluation of Airway Management and Splinting Techniques. (1984).

- Goutcher, C. M. & Lochhead, V. Reduction in mouth opening with semi-rigid cervical collars. Br. J. Anaesth. 95, 344–348 (2005).

- George, J. W., Fennema, J., Maddox, A., Nessler, M. & Skaggs, C. D. The effect of cervical spine manual therapy on normal mouth opening in asymptomatic subjects. J. Chiropr. Med. 6, 141–145 (2007).

- Benger, J. & Blackham, J. Why do we put cervical collars on conscious trauma patients? Scand. J. Trauma. Resusc. Emerg. Med.17, 44 (2009).

- Sundstrøm, T., Asbjørnsen, H., Habiba, S., Sunde, G. A. & Wester, K. Prehospital use of cervical collars in trauma patients: a critical review. J. Neurotrauma 31, 531–40 (2014).

The X Collar |

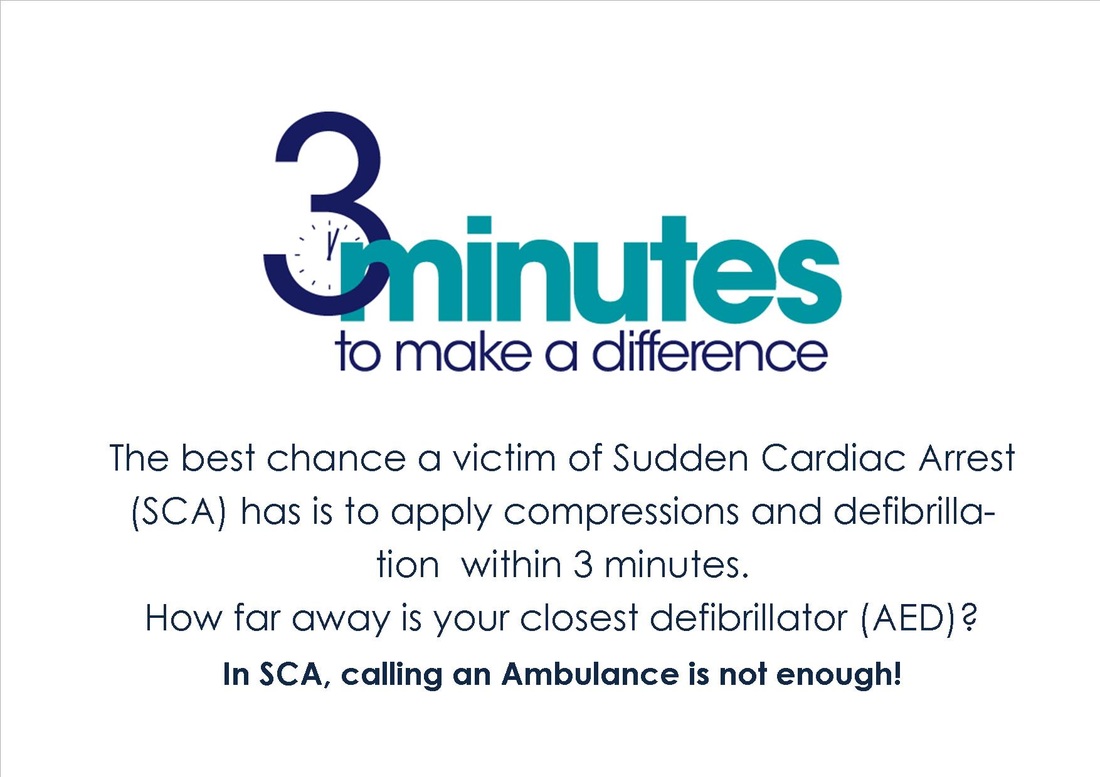

Who will win the "Australian - Fast Food AED Challenge"

A challenge open to all the major fast food chains in Australia. Be the first to install defibrillators (AED's) in your restaurants and get bragging rights.

With such huge profits being made in Australia by fast food companies and the importance of a balanced approach to food intake, now is the time for these retailers (who share 51.5 million visits a year in Australia) to show leadership in customer care and install defibrillators (AED's) in all their restaurants. This will help address the biggest single killer of Australians, Sudden Cardiac Arrest (SCA). Survival is less than 10% without an AED and up to 75% if the first shock is delivered in the first 3 minutes i.e. before Ambulance arrival.

With such huge profits being made in Australia by fast food companies and the importance of a balanced approach to food intake, now is the time for these retailers (who share 51.5 million visits a year in Australia) to show leadership in customer care and install defibrillators (AED's) in all their restaurants. This will help address the biggest single killer of Australians, Sudden Cardiac Arrest (SCA). Survival is less than 10% without an AED and up to 75% if the first shock is delivered in the first 3 minutes i.e. before Ambulance arrival.

"Hands only" CPR improves bystander willingness to start resuscitation by 70% in Sweden but in Australia bystanders are still encouraged to use "rescue breaths" in all resuscitation attempts?!

NEW ORLEANS – Since guidelines have endorsed the use of compression-only or Hands-Only CPR by people not trained or unwilling to provide rescue breaths during resuscitation attempts, Swedish bystanders are trying to help at a far greater rate.

Using a national registry in Sweden of 23,169 bystander-witnessed cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, researchers compared the total rate of bystander CPR attempted and the proportions of standard CPR , which involves both rescue breaths and chest compressions; and Hands-Only CPR.

They found: Bystanders attempted to resuscitate a total of 38 percent of people in cardiac arrest from 2000-2005 — before compressions-only-CPR was introduced into the guidelines. During 2006-2010 — after guidelines noted that dispatcher guidance of laypeople in compressions-only CPR might be preferable — 59 percent of bystanders attempted resuscitation CPR. The total rate of CPR attempts rose to 70 percent during 2011-2014, after guidelines strongly recommended that dispatchers instruct untrained bystanders in compressions-only-CPR.

Most of the increase in bystander CPR during the last 15 years in Sweden was associated with increased use of compressions-only-CPR, from 5 percent in 2000-2005 to 15 percent in 2006-2010 to 28 percent in 2011-2014. The 30-day survival of people with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was not significantly different between those receiving compressions-only-CPR (13.6 percent) and standard CPR (12.9 percent). Either approach resulted in far higher survival than when no CPR was attempted (6.4 percent during 2011-2014).

The study was presented Saturday at the Resuscitation Science Symposium taking place at American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2016.

An important lesson for the NSW Government on its attitude to AEDs in schools. Creating a regulatory framework is not removing barriers for schools wanting to purchase an AED!

|

Teachers save teenager's life after he goes into cardiac arrest at school

By MattJarram | Posted: December 13, 2016 - Nottingham Post A Nottinghamshire mum says quick-thinking staff saved her 17-year-old son's life after he suffered a sudden cardiac arrest while at school. Sarah Walker, 52, of Lingford, Cotgrave, says that if it wasn't for staff at South Nottinghamshire Academy, her son, Charlie Allison, would not be with them today. The keen Nottingham Forest supporter suddenly collapsed at 2.30pm on Friday while exercising in the school's Fitness Suite. The sports-mad pupil, who plays football for Bingham Town, had suffered a sudden cardiac arrest – and every moment was critical as school staff fought to save his life. The Radcliffe-on-Trent school has a defibrillator on site – which delivers a charge to the heart – and had just received whole school training on how to use the defib a week before Charlie collapsed. PE teacher, Scott Lowman, 31, and inclusion manager, Sam Proctor, 43, rushed to Charlie's aid and managed to bring the young lad back to life. The pair, assisted by pupils and staff, managed to start Charlie's heart before a road ambulance and the air ambulance arrived on site. Charlie's mother, Sarah Walker told the Post: "We owe the school Charlie's life. They gave us our son back. Without them I would not have a son. There is no doubt. Without the defibrillator he would not have made it to the hospital." In fact, the school said that Charlie, who is now recovering on the Acute Cardiac Ward at the City Hospital, was apparently most upset because his Nottingham Forest shirt had to be cut off while they worked on his heart. Explaining the ordeal, PE teacher Scott Lowman, who helped to save Charlie's life, told the Post: "One of the young lads in the fitness suite came running out and said Charlie had fainted. It was a scary situation. He started to go downhill – his breathing slowed and at one point stopped. "We shouted for the defibrillator after noticing his heart had stopped and I started CPR while waiting for the defibrillator. We delivered the shot which started Charlie's heart again. I am still struggling to come to terms with what has happened. Without the defibrillator he would not be here." Sam Proctor, who operated the defibrillator, added: "All of the school staff need praise. Everyone worked together to bring Charlie back to life." His mum says that Charlie has had no heart or breathing problems in the past and the family are anxiously waiting for a diagnosis following the close call. She said: "He is a fit and healthy boy. Charlie is a million miles away from where he was on Saturday and Sunday but he has a long way to recovery. We don't know what the diagnosis is yet. He is just a happy-go-lucky lad and very conscientious. Sport is his life and he lives and breathes sport." Charlie is undertaking a Level 3 Extended Diploma in Sport at the Academy in conjunction with Nottingham Forest. He has been a keen sportsman since he was six-years-old, making 144 appearances for Cotgrave Colts and playing for two years, mainly in right back, for Bingham Town. He is also in the Newark and Nottingham Cricket League for Keyworth Town and is a Nottingham Forest season ticket holder. Charlie has an older sister, Katie, 28. His mum, who is special needs teaching assistant at Oak Field School and Sports College, added: "I did not think I was ever going to see him again. Everyone went onto magic auto-pilot and brought him back to life." According to the British Heart Foundation, almost 90 percent of people who suffer out-of-hospital cardiac arrests die. The quick response was critical, as every minute without CPR and defibrillation reduces the chance of survival by up to 10 per cent. Dan Philpotts, head teacher at South Nottinghamshire Academy, said: "Our thoughts and best wishes are with Charlie and his family at this difficult time and we are so pleased to see him recovering in hospital. "Having seen first hand how a defibrillator helped saved Charlie's life, I cannot believe that they are not compulsory in schools and other public places. "South Nottinghamshire Academy staff were unbelievable and I am so proud of the way in which they responded – whilst it was very traumatic and some staff are struggling to come to terms with it, they can rest assured that they have contributed to saving a student's life." |

Stop Randomising all Cardiac Arrests

Myron L. Weisfeldt, MD

Read this paper from the American Heart Association's Circulation. 2016;134:2035-2036. on some of the issues with current and past cardiac arrest RCT research and the interpretration of outcomes. The author suggests that we may be missing important conclusions by randomizing all studies. <click here>

Public cardiopulmonary resuscitation training rates and awareness of hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a cross-sectional survey of Victorians.

Janet E Bray, Karen Smith, Rosalind Case, Susie Cartledge, Lahn Straney, Judith Finn

Emergency Medicine Australasia: EMA 2017 January 13

METHODS: A cross-sectional telephone survey in April 2016 of adult residents of the Australian state of Victoria was conducted. Primary outcomes were rates of CPR training and awareness of hands-only CPR.

RESULTS: Of the 404 adults surveyed (mean age 55 ± 17 years, 59% female, 73% metropolitan residents), 274 (68%) had undergone CPR training. Only 50% (n = 201) had heard of hands-only CPR, with most citing first-aid courses (41%) and media (36%) as sources of information.

RESULTS: Of the 404 adults surveyed (mean age 55 ± 17 years, 59% female, 73% metropolitan residents), 274 (68%) had undergone CPR training. Only 50% (n = 201) had heard of hands-only CPR, with most citing first-aid courses (41%) and media (36%) as sources of information.

ARAN Comment: The position taken by the ARC and its unofficial "spokespeople" ("unofficial", because the ARC refuses to debate the evidence with anyone outside their own organisation); is that the current DRSABCD appropriately prioritises compressions and defibrillation as the only two measures that have shown to make any difference in outcome in SCA in first response. The results of this study reinforce the position of ARAN; in that the message about compression-only CPR (which is the focus in all other jurisdictions in the world outside Australia and NZ) is not being articulated to the public in Australia. Half the population (even if they have been to a formal course or seen the propaganda from the ARC) have still not heard of compression only CPR being an alternative. All research on public willingness to help in an emergency shows an increased willingness if "rescue breaths" were omitted.

This survey would most likely have similar results in other states of Australia but will always show a huge variance to overseas, where the message is not hidden in an obsolete guideline for BLS (that is targeted to responding to hypoxic arrests). Another unfortunate (but predictable) fail from the ARC.

This survey would most likely have similar results in other states of Australia but will always show a huge variance to overseas, where the message is not hidden in an obsolete guideline for BLS (that is targeted to responding to hypoxic arrests). Another unfortunate (but predictable) fail from the ARC.

Association Between Tracheal Intubation During Adult In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest and Survival

Lars W Andersen, Asger Granfeldt, Clifton W Callaway, Steven M Bradley, Jasmeet Soar, Jerry P Nolan, Tobias Kurth, Michael W Donnino

JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association 2017 January 24

Importance: Tracheal intubation is common during adult in-hospital cardiac arrest, but little is known about the association between tracheal intubation and survival in this setting.

Objective: To determine whether tracheal intubation during adult in-hospital cardiac arrest is associated with survival to hospital discharge.

Design, Setting, and Participants: Observational cohort study of adult patients who had an in-hospital cardiac arrest from January 2000 through December 2014 included in the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation registry, a US-based multicenter registry of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Patients who had an invasive airway in place at the time of cardiac arrest were excluded. Patients intubated at any given minute (from 0-15 minutes) were matched with patients at risk of being intubated within the same minute (ie, still receiving resuscitation) based on a time-dependent propensity score calculated from multiple patient, event, and hospital characteristics.

Exposure: Tracheal intubation during cardiac arrest.

Main Outcomes and Measures: The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes included return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and a good functional outcome. A cerebral performance category score of 1 (mild or no neurological deficit) or 2 (moderate cerebral disability) was considered a good functional outcome.

Results: The propensity-matched cohort was selected from 108 079 adult patients at 668 hospitals. The median age was 69 years (interquartile range, 58-79 years), 45 073 patients (42%) were female, and 24 256 patients (22.4%) survived to hospital discharge. Of 71 615 patients (66.3%) who were intubated within the first 15 minutes, 43 314 (60.5%) were matched to a patient not intubated in the same minute. Survival was lower among patients who were intubated compared with those not intubated: 7052 of 43 314 (16.3%) vs 8407 of 43 314 (19.4%), respectively (risk ratio [RR] = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.81-0.87; P < .001). The proportion of patients with ROSC was lower among intubated patients than those not intubated: 25 022 of 43 311 (57.8%) vs 25 685 of 43 310 (59.3%), respectively (RR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.96-0.99; P < .001). Good functional outcome was also lower among intubated patients than those not intubated: 4439 of 41 868 (10.6%) vs 5672 of 41 733 (13.6%), respectively (RR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.75-0.81; P < .001). Although differences existed in prespecified subgroup analyses, intubation was not associated with improved outcomes in any subgroup.

Conclusions and Relevance: Among adult patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest, initiation of tracheal intubation within any given minute during the first 15 minutes of resuscitation, compared with no intubation during that minute, was associated with decreased survival to hospital discharge. Although the study design does not eliminate the potential for confounding by indication, these findings do not support early tracheal intubation for adult in-hospital cardiac arrest.

Lars W Andersen, Asger Granfeldt, Clifton W Callaway, Steven M Bradley, Jasmeet Soar, Jerry P Nolan, Tobias Kurth, Michael W Donnino

JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association 2017 January 24

Importance: Tracheal intubation is common during adult in-hospital cardiac arrest, but little is known about the association between tracheal intubation and survival in this setting.

Objective: To determine whether tracheal intubation during adult in-hospital cardiac arrest is associated with survival to hospital discharge.

Design, Setting, and Participants: Observational cohort study of adult patients who had an in-hospital cardiac arrest from January 2000 through December 2014 included in the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation registry, a US-based multicenter registry of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Patients who had an invasive airway in place at the time of cardiac arrest were excluded. Patients intubated at any given minute (from 0-15 minutes) were matched with patients at risk of being intubated within the same minute (ie, still receiving resuscitation) based on a time-dependent propensity score calculated from multiple patient, event, and hospital characteristics.

Exposure: Tracheal intubation during cardiac arrest.

Main Outcomes and Measures: The primary outcome was survival to hospital discharge. Secondary outcomes included return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and a good functional outcome. A cerebral performance category score of 1 (mild or no neurological deficit) or 2 (moderate cerebral disability) was considered a good functional outcome.

Results: The propensity-matched cohort was selected from 108 079 adult patients at 668 hospitals. The median age was 69 years (interquartile range, 58-79 years), 45 073 patients (42%) were female, and 24 256 patients (22.4%) survived to hospital discharge. Of 71 615 patients (66.3%) who were intubated within the first 15 minutes, 43 314 (60.5%) were matched to a patient not intubated in the same minute. Survival was lower among patients who were intubated compared with those not intubated: 7052 of 43 314 (16.3%) vs 8407 of 43 314 (19.4%), respectively (risk ratio [RR] = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.81-0.87; P < .001). The proportion of patients with ROSC was lower among intubated patients than those not intubated: 25 022 of 43 311 (57.8%) vs 25 685 of 43 310 (59.3%), respectively (RR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.96-0.99; P < .001). Good functional outcome was also lower among intubated patients than those not intubated: 4439 of 41 868 (10.6%) vs 5672 of 41 733 (13.6%), respectively (RR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.75-0.81; P < .001). Although differences existed in prespecified subgroup analyses, intubation was not associated with improved outcomes in any subgroup.

Conclusions and Relevance: Among adult patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest, initiation of tracheal intubation within any given minute during the first 15 minutes of resuscitation, compared with no intubation during that minute, was associated with decreased survival to hospital discharge. Although the study design does not eliminate the potential for confounding by indication, these findings do not support early tracheal intubation for adult in-hospital cardiac arrest.

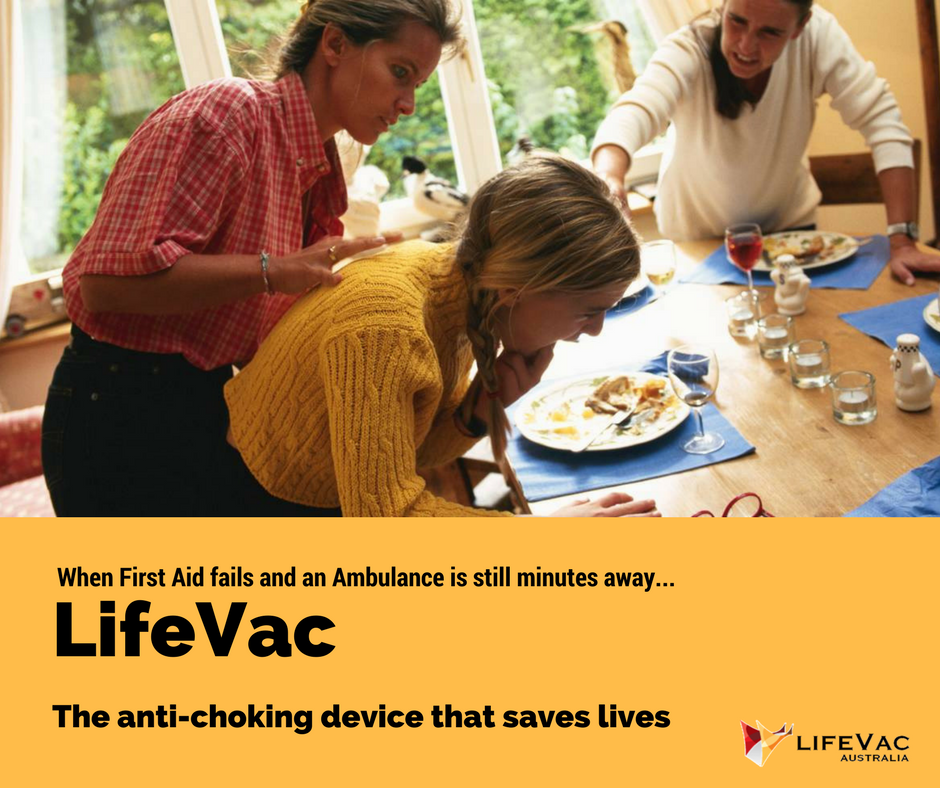

New Emergency Anti-Choking Device - LifeVac now available in Australia

Designed to be used when first aid fails, the LifeVac has already saved 6 lives. The device comes in two configurations. The first for home or facility use that can be wall mounted. The other for storage in existing kits for use by first responders and paramedics. The device can also be used on yourself.

As a comparison, the ARC, one-handed chest thrusts technique for the relief of upper airway obstruction in the conscious adult, rather than abdominal thrusts (used in every country in the world other than AU and NZ) has no relevant clinical evidence, has no clinical trials and has no recorded examples of success in over 15 years of its inception. This is one of the reasons LifeVac saw Australia as a country in need of a device such as the LifeVac.

If we compare the evidence to support LifeVac with the ARC recommendation of one-handed chest thrusts technique:

LifeVac ARC Recommendation

Cadaver Studies Yes No

Manikin Studies Yes No

Used Internationally Yes No

Evidence of Success Yes No

(Note: The studies conducted by LifeVac on our device are available on the website www.lifevac.net.au)

Considering the comparison table above and the level of evidence required to suggest “best practice” it is surprising that this device is not more widespread in Australia over unproven recommendations. Disappointing, but again so predictably when it comes to innovation that trumps their consensus opinion, the ARC refused to allow this new technology to be presented at their recent Spark of Life Conference. Reinforcing again the ARC focus on politics and monopoly control rather than saving lives.

ARAN fully endorses the LifeVac anti-choking device for the removal of upper airway obstruction after the failure of first aid measures. In making this determination, ARAN notes that the device has more evidence of efficacy than the ARC "one-handed chest thrusts technique", currently recommended by the ARC over abdominal thrusts.

As a comparison, the ARC, one-handed chest thrusts technique for the relief of upper airway obstruction in the conscious adult, rather than abdominal thrusts (used in every country in the world other than AU and NZ) has no relevant clinical evidence, has no clinical trials and has no recorded examples of success in over 15 years of its inception. This is one of the reasons LifeVac saw Australia as a country in need of a device such as the LifeVac.

If we compare the evidence to support LifeVac with the ARC recommendation of one-handed chest thrusts technique:

LifeVac ARC Recommendation

Cadaver Studies Yes No

Manikin Studies Yes No

Used Internationally Yes No

Evidence of Success Yes No

(Note: The studies conducted by LifeVac on our device are available on the website www.lifevac.net.au)

Considering the comparison table above and the level of evidence required to suggest “best practice” it is surprising that this device is not more widespread in Australia over unproven recommendations. Disappointing, but again so predictably when it comes to innovation that trumps their consensus opinion, the ARC refused to allow this new technology to be presented at their recent Spark of Life Conference. Reinforcing again the ARC focus on politics and monopoly control rather than saving lives.

ARAN fully endorses the LifeVac anti-choking device for the removal of upper airway obstruction after the failure of first aid measures. In making this determination, ARAN notes that the device has more evidence of efficacy than the ARC "one-handed chest thrusts technique", currently recommended by the ARC over abdominal thrusts.

36 US States now require high school students to learn CPR prior to graduation. 0 Australian states require students to learn CPR prior to graduation (FAIL)

South Dakota has become the latest US state that requires high school students to learn CPR (including defibrillation) prior to graduation

http://news.heart.org/south-dakota-becomes-36th-state-to-require-cpr-to-graduate-high-school/

South Dakota has become the latest US state that requires high school students to learn CPR (including defibrillation) prior to graduation

http://news.heart.org/south-dakota-becomes-36th-state-to-require-cpr-to-graduate-high-school/

ARAN released draft of new ASHPA - Universal BLS Emergency Guideine

For years the DRSABCD (with minor tweaks) has been the standard advice when approaching any BLS emergency. However since its inception there has also been a sense amongst those who have had to use or teach this guideline that it is not a good fit for emergencies that are not a collapse and provides no overall guidance for managing any other type of incident. The other issue is that even if used in a collapse the DRSABCD provides guidance about providing care to a hypoxic arrest in an otherwise healthy casualty - a scenario that really happens. We have found at least 10 advantages of the ASHPA Guideline over the DRSABCD and you may find more. The ASHPA also builds on the 2 critical questions in BLS (consciousness/ unconsciousness and if breathing is normal) to guide the next steps, regardless of the emergency.

Check it out in our "Flowcharts" section

Check it out in our "Flowcharts" section

Compression-to-Ventilation Ratio and Incidence of Rearrest - A Secondary Analysis of the ROC CCC Trial.

A new look at continuous compressions vs. the 30:2 ratio and if CCC produces better, worse or comparable rates of rearrest post ROSC.

NEW UK Resuscitation Council AED Posters and Signs.

After a national survey of consumers, the UK Resuscitation Council has released new posters and signs for AEDs. The content, although not clinically accurate was the consensus among consumers of the easiest messages about AED to understand. ARAN has change the emergency number to 000 and the material is now available for download in pdf.

New cheaper competitor to Epipen coming later this year.

This photo provided by Adamis Pharmaceuticals Corp. shows the Symjepi syringe, prefilled with the hormone epinephrine, which helps stop life-threatening allergic reactions from insect stings and bites or eating foods such as nuts and eggs. On Thursday, June 15, 2017, the Food and Drug Administration approved the Adamis Pharmaceuticals Corp. product, which is expected to go on sale later in 2017. (Audacity Health/Courtesy of Adamis Pharmaceuticals Corp. via AP)

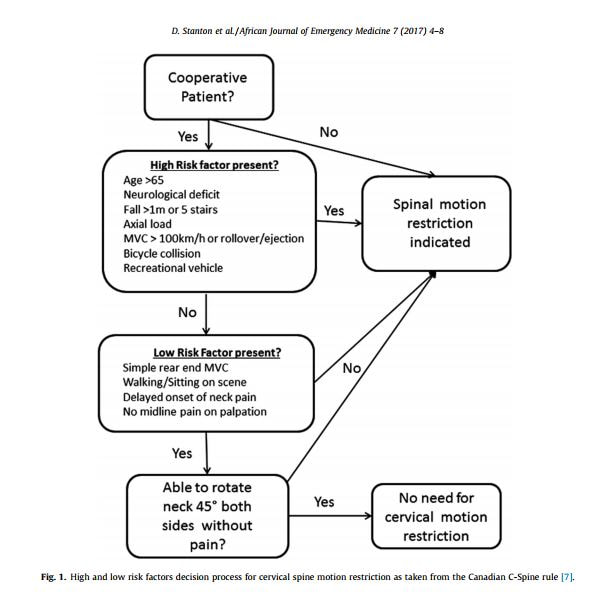

African Journal of Emergency Medicine

Cervical collars and immobilisation: A South African best practice recommendation

Quality of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation during real-life out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Tore Gyllenborg, Asger Granfeldt, Freddy Lippert, Ingunn Skogstad Riddervold, Fredrik Folke

Resuscitation 2017 September 10

This study conducted in the Capital Region, Denmark, (2012-2016) the initial 10 minutes of CPR data were analysed for compression rate, depth, fraction and compressions delivered for each minute of CPR. Data are presented as median [25th;75th percentile]. The study included 136 cases. Bystander median compression rate was 101min (-1) [94;113], compression depth was 48mm [3.9;5.8] and compressions per minute were 62 [48;73]. Of all cases, the median compression rate was 100-120min (-1) in 42%, compression depth was 50 -60mm (i.e in compliance with current recommendations) in 26%, compression fraction≥60% in 51% and compressions delivered per minute exceeded 60 in 54%. In a minute-to-minute analysis, the found no evidence of deterioration in CPR quality over time. The median peri-shock pause was 27s [23;31] and the pre-shock pause was 19s [17;22].

CONCLUSION: The median CPR performed by bystanders using AEDs with audio-feedback in OHCA was within guideline recommendations without deterioration over time. Compression depth had poorer quality compared with other parameters. To improve bystander CPR quality, focus should be on proper compression depth and minimizing pauses.

ARAN Comment: This data (although from an AED using a accellerometer feedback) reinforces the importance of compression depth (as only 42% were in the recommended range). Unfortunately, most training manikins (that are under no standard), do not realistically simulated the force pressure required for compressions on a typical cardiac arrest victim. Two recommendations would be: 1. A standard for resuscitation manikins and 2. Training emphasis on the minimisation of pauses e.g. high performance cpr.

CONCLUSION: The median CPR performed by bystanders using AEDs with audio-feedback in OHCA was within guideline recommendations without deterioration over time. Compression depth had poorer quality compared with other parameters. To improve bystander CPR quality, focus should be on proper compression depth and minimizing pauses.

ARAN Comment: This data (although from an AED using a accellerometer feedback) reinforces the importance of compression depth (as only 42% were in the recommended range). Unfortunately, most training manikins (that are under no standard), do not realistically simulated the force pressure required for compressions on a typical cardiac arrest victim. Two recommendations would be: 1. A standard for resuscitation manikins and 2. Training emphasis on the minimisation of pauses e.g. high performance cpr.

Frequency and influencing factors of cardiopulmonary resuscitation-related injuries during implementation of the American Heart Association 2010 Guidelines: a retrospective study based on autopsy and postmortem computed tomography. Rutsuko Yamaguchi, Yohsuke Makino, Fumiko Chiba, Suguru Torimitsu, Daisuke Yajima, Go Inokuchi, Ayumi Motomura, Mari Hashimoto, Yumi Hoshioka, Tomohiro Shinozaki, Hirotaro Iwase

International Journal of Legal Medicine 2017 September 13

The study conducted between January 2012 to December 2014 tried to determine the frequency of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)-related injuries and factors involved in their occurrence, data based on forensic autopsy and postmortem computed tomography (PMCT) during implementation of the 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for CPR were studied.

RESULTS: In total, 180 consecutive cases were analyzed. Rib fractures and sternal fractures were most frequent (overall frequency, 66.1 and 52.8%, respectively), followed by heart injuries (12.8%) and abdominal visceral injuries (2.2%). Urgently life-threatening injuries were rare (2.8%). Older age was an independent risk factor for rib fracture [adjusted odds ratio (AOR), 1.06; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.04-1.08; p < 0.001], ≥ 3 rib fractures (AOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02-1.09; p = 0.002), and sternal fracture (AOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05; p < 0.001). Female sex was significantly associated with sternal fracture (AOR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.02-4.25; p = 0.04). Chest compression only by laypersons was inversely associated with rib and sternal fractures. Body mass index and in-hospital cardiac arrest were not significantly associated with any complications. The frequency of thoracic skeletal injuries was similar to that in recent autopsy-based studies.

ARAN Comment: The significant findings of low numbers of injuries is consistent with other findings. The association of age and musculo-skeletal injuries is self evident. The significant finding was that chest compression only CPR by bystanders was inversely associated with complications like rib and sternal fractures. This is further evidence that compression only CPR is a superior method for public BLS training, particularly in the first 6-8 minutes in SCA.

RESULTS: In total, 180 consecutive cases were analyzed. Rib fractures and sternal fractures were most frequent (overall frequency, 66.1 and 52.8%, respectively), followed by heart injuries (12.8%) and abdominal visceral injuries (2.2%). Urgently life-threatening injuries were rare (2.8%). Older age was an independent risk factor for rib fracture [adjusted odds ratio (AOR), 1.06; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.04-1.08; p < 0.001], ≥ 3 rib fractures (AOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02-1.09; p = 0.002), and sternal fracture (AOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05; p < 0.001). Female sex was significantly associated with sternal fracture (AOR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.02-4.25; p = 0.04). Chest compression only by laypersons was inversely associated with rib and sternal fractures. Body mass index and in-hospital cardiac arrest were not significantly associated with any complications. The frequency of thoracic skeletal injuries was similar to that in recent autopsy-based studies.

ARAN Comment: The significant findings of low numbers of injuries is consistent with other findings. The association of age and musculo-skeletal injuries is self evident. The significant finding was that chest compression only CPR by bystanders was inversely associated with complications like rib and sternal fractures. This is further evidence that compression only CPR is a superior method for public BLS training, particularly in the first 6-8 minutes in SCA.

Association of Public Health Initiatives With Outcomes for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest at Home and in Public Locations

Christopher B Fordyce, Carolina M Hansen, Kristian Kragholm, Matthew E Dupre, James G Jollis, Mayme L Roettig, Lance B Becker, Steen M Hansen, Tomoya T Hinohara, Claire C Corbett, Lisa Monk, R Darrell Nelson, David A Pearson, Clark Tyson, Sean van Diepen, Monique L Anderson, Bryan McNally, Christopher B Granger

JAMA Cardiology 2017 October 4

Importance: Little is known about the influence of comprehensive public health initiatives according to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) location, particularly at home, where resuscitation efforts and outcomes have historically been poor.

Objective: To describe temporal trends in bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and first-responder defibrillation for OHCAs stratified by home vs public location and their association with survival and neurological outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants: This observational study reviewed 8269 patients with OHCAs (5602 [67.7%] at home and 2667 [32.3%] in public) for whom resuscitation was attempted using data from the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES) from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2014. The setting was 16 counties in North Carolina.

Exposures: Patients were stratified by home vs public OHCA. Public health initiatives to improve bystander and first-responder interventions included training members of the general population in CPR and in the use of automated external defibrillators, teaching first responders about team-based CPR (eg, automated external defibrillator use and high-performance CPR), and instructing dispatch centres on recognition of cardiac arrest.

Main Outcomes and Measures: Association of resuscitation efforts with survival and neurological outcomes from 2010 through 2014.

Results: Among home OHCA patients (n = 5602), the median age was 64 years, and 62.2% were male; among public OHCA patients (n = 2667), the median age was 68 years, and 61.5% were male. After comprehensive public health initiatives, the proportion of patients receiving bystander CPR increased at home (from 28.3% [275 of 973] to 41.3% [498 of 1206], P < .001) and in public (from 61.0% [275 of 451] to 70.5% [424 of 601], P = .01), while first-responder defibrillation increased at home (from 42.2% [132 of 313] to 50.8% [212 of 417], P = .02) but not significantly in public (from 33.1% [58 of 175] to 37.8% [93 of 246], P = .17). Survival to discharge improved for arrests at home (from 5.7% [60 of 1057] to 8.1% [100 of 1238], P = .047) and in public (from 10.8% [50 of 464] to 16.2% [98 of 604], P = .04). Compared with emergency medical services-initiated CPR and resuscitation, patients with home OHCA were significantly more likely to survive to hospital discharge if they received bystander-initiated CPR and first-responder defibrillation (odds ratio, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.01-2.38). Patients with arrests in public were most likely to survive if they received both bystander-initiated CPR and defibrillation (odds ratio, 4.33; 95% CI, 2.11-8.87).

Conclusions and Relevance: After coordinated and comprehensive public health initiatives, more patients received bystander CPR and first-responder defibrillation at home and in public, which was associated with improved survival.

ARAN Comment:: Whilst the outcomes of this research are predictable and obvious we in Australia see not State or Federal Government interest in OHCA through public education and initiative. The NHS in the UK funds defibrillators in communities. In Australia the emphasis is on Ambulance and ED's saving lives in OHCA., however the pre-Ambulance phase is where we can see the real improvements. to our appalling survival rate. (5-6% to hospital discharge in Adults). i.e. only 1,980 lives out of 33,500 (and up to 75% are savable). Road fatalities only account for 1.,155 deaths a year and have been relatively static of the past 7 years (regardless of the heavy policing of marginal speed infringements, speed cameras, television advertising, double demerits and all the public advertising . Road safety campaigns and processes cost over $500 million dollars per year in Australia i.e nearly 1/2 a million dollars for every death. ARAN has written to both State and Federal Health Ministers concerning improving the national situation, however it has been made very clear that there is no appetite or interest in OHCA in Australian government.

Continuous chest compression versus interrupted chest compression for cardiopulmonary resuscitation of non-asphyxial out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

Lei Zhan, Li J Yang, Yu Huang, Qing He, Guan J Liu

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017 March 27, 3: CD010134

BACKGROUND: Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major cause of death worldwide. Cardiac arrest can be subdivided into asphyxial and non asphyxial etiologies. An asphyxia arrest is caused by lack of oxygen in the blood and occurs in drowning and choking victims and in other circumstances. A non asphyxial arrest is usually a loss of functioning cardiac electrical activity. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a well-established treatment for cardiac arrest. Conventional CPR includes both chest compressions and 'rescue breathing' such as mouth-to-mouth breathing. Rescue breathing is delivered between chest compressions using a fixed ratio, such as two breaths to 30 compressions or can be delivered asynchronously without interrupting chest compression. Studies show that applying continuous chest compressions is critical for survival and interrupting them for rescue breathing might increase risk of death. Continuous chest compression CPR may be performed with or without rescue breathing.

OBJECTIVES: To assess the effects of continuous chest compression CPR (with or without rescue breathing) versus conventional CPR plus rescue breathing (interrupted chest compression with pauses for breaths) of non-asphyxial OHCA.

SEARCH METHODS: We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 1 2017); MEDLINE (Ovid) (from 1985 to February 2017); Embase (1985 to February 2017); Web of Science (1985 to February 2017). We searched ongoing trials databases including controlledtrials.com and clinicaltrials.gov. We did not impose any language or publication restrictions.

SELECTION CRITERIA: We included randomized and quasi-randomized studies in adults and children suffering non-asphyxial OHCA due to any cause. Studies compared the effects of continuous chest compression CPR (with or without rescue breathing) with interrupted CPR plus rescue breathing provided by rescuers (bystanders or professional CPR providers).

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS: Two authors extracted the data and summarized the effects as risk ratios (RRs), adjusted risk differences (ARDs) or mean differences (MDs). We assessed the quality of evidence using GRADE.

MAIN RESULTS: We included three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and one cluster-RCT (with a total of 26,742 participants analysed). We identified one ongoing study. While predominantly adult patients, one study included children. Untrained bystander-administered CPR. Three studies assessed CPR provided by untrained bystanders in urban areas of the USA, Sweden and the UK. Bystanders administered CPR under telephone instruction from emergency services. There was an unclear risk of selection bias in two trials and low risk of detection, attrition, and reporting bias in all three trials. Survival outcomes were unlikely to be affected by the unblinded design of the studies.We found high-quality evidence that continuous chest compression CPR without rescue breathing improved participants' survival to hospital discharge compared with interrupted chest compression with pauses for rescue breathing (ratio 15:2) by 2.4% (14% versus 11.6%; RR 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01 to 1.46; 3 studies, 3031 participants).One trial reported survival to hospital admission, but the number of participants was too low to be certain about the effects of the different treatment strategies on survival to admission(RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.48; 1 study, 520 participants; moderate-quality evidence).There were no data available for survival at one year, quality of life, return of spontaneous circulation or adverse effects.There was insufficient evidence to determine the effect of the different strategies on neurological outcomes at hospital discharge (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.66; 1 study, 1286 participants; moderate-quality evidence). The proportion of participants categorized as having good or moderate cerebral performance was 11% following treatment with interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing compared with 10% to 18% for those treated with continuous chest compression CPR without rescue breathing. CPR administered by a trained professional In one trial that assessed OHCA CPR administered by emergency medical service professionals (EMS) 23,711 participants received either continuous chest compression CPR (100/minute) with asynchronous rescue breathing (10/minute) or interrupted chest compression with pauses for rescue breathing (ratio 30:2). The study was at low risk of bias overall.After OHCA, risk of survival to hospital discharge is probably slightly lower for continuous chest compression CPR with asynchronous rescue breathing compared with interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing (9.0% versus 9.7%) with an adjusted risk difference (ARD) of -0.7%; 95% CI (-1.5% to 0.1%); moderate-quality evidence.There is high-quality evidence that survival to hospital admission is 1.3% lower with continuous chest compression CPR with asynchronous rescue breathing compared with interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing (24.6% versus 25.9%; ARD -1.3% 95% CI (-2.4% to -0.2%)).Survival at one year and quality of life were not reported.Return of spontaneous circulation is likely to be slightly lower in people treated with continuous chest compression CPR plus asynchronous rescue breathing (24.2% versus 25.3%; -1.1% (95% CI -2.4 to 0.1)), high-quality evidence.There is high-quality evidence of little or no difference in neurological outcome at discharge between these two interventions (7.0% versus 7.7%; ARD -0.6% (95% CI -1.4 to 0.1).Rates of adverse events were 54.4% in those treated with continuous chest compressions plus asynchronous rescue breathing versus 55.4% in people treated with interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing compared with the ARD being -1% (-2.3 to 0.4), moderate-quality evidence).

AUTHORS' CONCLUSIONS: Following OHCA, we have found that bystander-administered chest compression-only CPR, supported by telephone instruction, increases the proportion of people who survive to hospital discharge compared with conventional interrupted chest compression CPR plus rescue breathing. Some uncertainty remains about how well neurological function is preserved in this population and there is no information available regarding adverse effects.When CPR was performed by EMS providers, continuous chest compressions plus asynchronous rescue breathing did not result in higher rates for survival to hospital discharge compared to interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing. The results indicate slightly lower rates of survival to admission or discharge, favourable neurological outcome and return of spontaneous circulation observed following continuous chest compression. Adverse effects are probably slightly lower with continuous chest compression.Increased availability of automated external defibrillators (AEDs), and AED use in CPR need to be examined, and also whether continuous chest compression CPR is appropriate for paediatric cardiac arrest.

ARAN Comment: The study reinforces the benefits of continuous compressions over interrupted compressions, however as with most research does not differentiate between protected vs. unprotected airways and bystander vs. professional intervention and the timing of the onset of different strategies e.g. only on paramedic arrival, from the witnessed event and by whom. These confounders tend to muddy the importance of any findings. The results of the conflation of these variables is often interpreted as inconclusive evidence on which to base change. The significant improvement of cerebral function of those treated with continuous compressions by professionals (18%) over (11%) with current interrupted compressions is an important finding. By inference, the other factor here is that these patients (as they were treated by professionals) would have had a protected airway and not hyperventilated. Again a distinction in management and rescuer would be helpful and probably show a much clearer distinction for change to current recommendations (especially in Australia). The other confounder is that the bystander ability to discern the aetiology of the arrest. The conclusion is once again clear, compression only CPR for bystanders, prior to paramedic arrival leads to better outcomes, particularly in SCA. It is astounding that we have known this since at least 2010 but in Australia we (not all just those looking to for guidelines) are still holding on to an ideology that most arrest are hypoxic in nature and only happen to healthy victims.

Lei Zhan, Li J Yang, Yu Huang, Qing He, Guan J Liu

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017 March 27, 3: CD010134

BACKGROUND: Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major cause of death worldwide. Cardiac arrest can be subdivided into asphyxial and non asphyxial etiologies. An asphyxia arrest is caused by lack of oxygen in the blood and occurs in drowning and choking victims and in other circumstances. A non asphyxial arrest is usually a loss of functioning cardiac electrical activity. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a well-established treatment for cardiac arrest. Conventional CPR includes both chest compressions and 'rescue breathing' such as mouth-to-mouth breathing. Rescue breathing is delivered between chest compressions using a fixed ratio, such as two breaths to 30 compressions or can be delivered asynchronously without interrupting chest compression. Studies show that applying continuous chest compressions is critical for survival and interrupting them for rescue breathing might increase risk of death. Continuous chest compression CPR may be performed with or without rescue breathing.

OBJECTIVES: To assess the effects of continuous chest compression CPR (with or without rescue breathing) versus conventional CPR plus rescue breathing (interrupted chest compression with pauses for breaths) of non-asphyxial OHCA.

SEARCH METHODS: We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 1 2017); MEDLINE (Ovid) (from 1985 to February 2017); Embase (1985 to February 2017); Web of Science (1985 to February 2017). We searched ongoing trials databases including controlledtrials.com and clinicaltrials.gov. We did not impose any language or publication restrictions.

SELECTION CRITERIA: We included randomized and quasi-randomized studies in adults and children suffering non-asphyxial OHCA due to any cause. Studies compared the effects of continuous chest compression CPR (with or without rescue breathing) with interrupted CPR plus rescue breathing provided by rescuers (bystanders or professional CPR providers).

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS: Two authors extracted the data and summarized the effects as risk ratios (RRs), adjusted risk differences (ARDs) or mean differences (MDs). We assessed the quality of evidence using GRADE.

MAIN RESULTS: We included three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and one cluster-RCT (with a total of 26,742 participants analysed). We identified one ongoing study. While predominantly adult patients, one study included children. Untrained bystander-administered CPR. Three studies assessed CPR provided by untrained bystanders in urban areas of the USA, Sweden and the UK. Bystanders administered CPR under telephone instruction from emergency services. There was an unclear risk of selection bias in two trials and low risk of detection, attrition, and reporting bias in all three trials. Survival outcomes were unlikely to be affected by the unblinded design of the studies.We found high-quality evidence that continuous chest compression CPR without rescue breathing improved participants' survival to hospital discharge compared with interrupted chest compression with pauses for rescue breathing (ratio 15:2) by 2.4% (14% versus 11.6%; RR 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01 to 1.46; 3 studies, 3031 participants).One trial reported survival to hospital admission, but the number of participants was too low to be certain about the effects of the different treatment strategies on survival to admission(RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.48; 1 study, 520 participants; moderate-quality evidence).There were no data available for survival at one year, quality of life, return of spontaneous circulation or adverse effects.There was insufficient evidence to determine the effect of the different strategies on neurological outcomes at hospital discharge (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.66; 1 study, 1286 participants; moderate-quality evidence). The proportion of participants categorized as having good or moderate cerebral performance was 11% following treatment with interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing compared with 10% to 18% for those treated with continuous chest compression CPR without rescue breathing. CPR administered by a trained professional In one trial that assessed OHCA CPR administered by emergency medical service professionals (EMS) 23,711 participants received either continuous chest compression CPR (100/minute) with asynchronous rescue breathing (10/minute) or interrupted chest compression with pauses for rescue breathing (ratio 30:2). The study was at low risk of bias overall.After OHCA, risk of survival to hospital discharge is probably slightly lower for continuous chest compression CPR with asynchronous rescue breathing compared with interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing (9.0% versus 9.7%) with an adjusted risk difference (ARD) of -0.7%; 95% CI (-1.5% to 0.1%); moderate-quality evidence.There is high-quality evidence that survival to hospital admission is 1.3% lower with continuous chest compression CPR with asynchronous rescue breathing compared with interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing (24.6% versus 25.9%; ARD -1.3% 95% CI (-2.4% to -0.2%)).Survival at one year and quality of life were not reported.Return of spontaneous circulation is likely to be slightly lower in people treated with continuous chest compression CPR plus asynchronous rescue breathing (24.2% versus 25.3%; -1.1% (95% CI -2.4 to 0.1)), high-quality evidence.There is high-quality evidence of little or no difference in neurological outcome at discharge between these two interventions (7.0% versus 7.7%; ARD -0.6% (95% CI -1.4 to 0.1).Rates of adverse events were 54.4% in those treated with continuous chest compressions plus asynchronous rescue breathing versus 55.4% in people treated with interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing compared with the ARD being -1% (-2.3 to 0.4), moderate-quality evidence).

AUTHORS' CONCLUSIONS: Following OHCA, we have found that bystander-administered chest compression-only CPR, supported by telephone instruction, increases the proportion of people who survive to hospital discharge compared with conventional interrupted chest compression CPR plus rescue breathing. Some uncertainty remains about how well neurological function is preserved in this population and there is no information available regarding adverse effects.When CPR was performed by EMS providers, continuous chest compressions plus asynchronous rescue breathing did not result in higher rates for survival to hospital discharge compared to interrupted chest compression plus rescue breathing. The results indicate slightly lower rates of survival to admission or discharge, favourable neurological outcome and return of spontaneous circulation observed following continuous chest compression. Adverse effects are probably slightly lower with continuous chest compression.Increased availability of automated external defibrillators (AEDs), and AED use in CPR need to be examined, and also whether continuous chest compression CPR is appropriate for paediatric cardiac arrest.

ARAN Comment: The study reinforces the benefits of continuous compressions over interrupted compressions, however as with most research does not differentiate between protected vs. unprotected airways and bystander vs. professional intervention and the timing of the onset of different strategies e.g. only on paramedic arrival, from the witnessed event and by whom. These confounders tend to muddy the importance of any findings. The results of the conflation of these variables is often interpreted as inconclusive evidence on which to base change. The significant improvement of cerebral function of those treated with continuous compressions by professionals (18%) over (11%) with current interrupted compressions is an important finding. By inference, the other factor here is that these patients (as they were treated by professionals) would have had a protected airway and not hyperventilated. Again a distinction in management and rescuer would be helpful and probably show a much clearer distinction for change to current recommendations (especially in Australia). The other confounder is that the bystander ability to discern the aetiology of the arrest. The conclusion is once again clear, compression only CPR for bystanders, prior to paramedic arrival leads to better outcomes, particularly in SCA. It is astounding that we have known this since at least 2010 but in Australia we (not all just those looking to for guidelines) are still holding on to an ideology that most arrest are hypoxic in nature and only happen to healthy victims.

Technique for chest compressions in adult CPR

Taufiek K Rajab, Charles N Pozner, Claudius Conrad, Lawrence H Cohn, and Jan D Schmitto

Abstract: Chest compressions have saved the lives of countless patients in cardiac arrest as they generate a small but critical amount of blood flow to the heart and brain. This is achieved by direct cardiac massage as well as a thoracic pump mechanism. In order to optimize blood flow excellent chest compression technique is critical. Thus, the quality of the delivered chest compressions is a pivotal determinant of successful resuscitation. If a patient is found unresponsive without a definite pulse or normal breathing then the responder should assume that this patient is in cardiac arrest, activate the emergency response system and immediately start chest compressions. Contra-indications to starting chest compressions include a valid Do Not Attempt Resuscitation Order. Optimal technique for adult chest compressions includes positioning the patient supine, and pushing hard and fast over the center of the chest with the outstretched arms perpendicular to the patient's chest. The rate should be at least 100 compressions per minute and any interruptions should be minimized to achieve a minimum of 60 actually delivered compressions per minute. Aggressive rotation of compressors prevents decline of chest compression quality due to fatigue. Chest compressions are terminated following return of spontaneous circulation. Unconscious patients with normal breathing are placed in the recovery position. If there is no return of spontaneous circulation, then the decision to terminate chest compressions is based on the clinical judgment that the patient's cardiac arrest is unresponsive to treatment. Finally, it is important that family and patients' loved ones who witness chest compressions be treated with consideration and sensitivity.

Introduction: Chest compressions have saved the lives of countless patients in cardiac arrest since they were first introduced in 1960 [1]. Cardiac arrest is treated with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and chest compressions are a basic component of CPR. The quality of the delivered chest compressions is a pivotal determinant of successful resuscitation [2]. In spite of this, studies show that the quality of chest compressions, even if delivered by healthcare professionals, is often suboptimal [2]. Therefore it is important that providers carefully familiarize themselves with this technique.

Indications: Chest compressions are generally indicated for all patients in cardiac arrest. Unlike other medical interventions, chest compressions can be initiated by any healthcare provider without a physician's order. This is based on implied patient consent for emergency treatment [3]. If a patient is found unresponsive without a definite pulse or normal breathing then the responder should assume that this patient is in cardiac arrest, activate the emergency response system and immediately start chest compressions [4]. The risk of serious injury from chest compressions to patients who are not in cardiac arrest is negligible [5], while any delay in starting chest compressions has grave implications for outcome. Due to the importance of starting chest compressions early, pulse and breathing checks were de-emphasized in the most recent CPR guidelines [4]. Thus, healthcare providers should take no longer than 10 seconds to check for a pulse. The carotid or femoral pulses are preferred locations for pulse checks since peripheral arteries can be unreliable.

Contraindications: In certain circumstances it is inappropriate to initiate chest compressions. A valid Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order that prohibits chest compressions is an absolute contra-indication. DNR orders are considered by the attending physician on the basis of patient autonomy and treatment futility.

The principle of patient autonomy dictates that competent patients have a right to refuse medical treatment [6]. Therefore a DNR order should be documented if patients do not wish to be treated with chest compressions. For patients with impaired decision-making, previous preferences should be taken into account when making decisions regarding DNR.

The principle of treatment futility dictates that healthcare providers are not obliged to provide treatment if this would be futile [6]. Therefore a DNR order should be documented if chest compressions would be unlikely to confer a survival benefit or acceptable quality of life. However, few criteria can reliably predict the futility of starting chest compressions.

If there is any uncertainty regarding DNR status then chest compressions should be started immediately while the uncertainties are addressed. Compressions may subsequently be terminated as soon as a valid DNR order is produced.

Of note, patients with implantable left ventricular assist devices [7-9] or patients with total artificial hearts or biventricular assist devices [10] who suffer cardiac arrest from device failure should be resuscitated using a backup pump (e.g. ECMO [11,12]) if this is available rather than with chest compressions.

The Physiology of Chest Compressions: Chest compressions generate a small but critical amount of blood flow to the heart and brain. This significantly improves the chances of successful resuscitation [13]. However, the precise mechanism of blood flow during chest compressions has been controversial since the 1960s. The two main hypotheses are the external cardiac massage model and the thoracic pump model.

The external cardiac massage model suggests that chest compressions directly compress the heart between the depressed sternum and the thoracic spine [1]. This ejects blood into the systemic and pulmonary circulations while backward flow during decompression is limited by the cardiac valves. The external cardiac massage model is supported by radiographic evidence of direct compression of cardiac structures during chest compressions [14].

The thoracic pump model suggests that chest compressions intermittently increase global intra-thoracic pressure, with equivalent pressures exerted on vena cava, the heart and the aorta [9]. Thus blood is ejected retrograde from the intra-thoracic venous vasculature as well as antegrade from the intra-thoracic arterial vasculature and both arterial as well as venous pressures rise concomitantly. Therefore the presence of an arterial pulse in itself is not a reliable indicator of blood flow. This principle is illustrated by the fact that a ligated artery will continue to pulsate even in the absence of blood flow. However, the compliance of venous capacitance vessels is greater than the compliance of arterial resistance vessels. Therefore a pressure differential between the extra-thoracic arterial and venous sides of the vascular tree is formed. This pressure differential is but a fraction of the arterial pulse pressure, yet it is sufficient to drive some blood flow. The thoracic pump model is supported by arterial and venous pressure tracings demonstrating simultaneous peaks in venous and arterial pressures during chest compressions [15].

In toto, the available evidence suggests that both cardiac massage and the thoracic pump contribute to blood flow during chest compressions. Yet even excellent chest compressions can only generate a fraction of baseline blood flow [16]. Therefore the time during chest compressions contributes to the ongoing ischemic insult to the patient's heart and brain.

The brain is the organ most susceptible to decreased blood flow and suffers irreversible damage within 5 minutes of absent perfusion. The myocardium is the second most susceptible organ, with ROSC directly related to coronary perfusion pressures [17]. Therefore successful resuscitation with neurologically intact survival and ROSC critically depends on maintaining blood flow to the heart and brain via chest compressions.

Technique for Chest Compression: Chest compressions consist of forceful and fast oscillations of the lower half of the sternum [1]. The technique of delivering chest compressions is highly standardized and based on international consensus that is updated in 5-year intervals [4,13,18].

Patient PositioningThe patient in cardiac arrest should be placed in supine position with the rescuer standing beside the patient's bed or kneeling beside the patient's chest [18]. Adjustment of the bed height or standing on a stool allows leveraging the body weight above the waist for mechanical advantage. For optimal transfer of energy during chest compressions the patient should be positioned on a firm surface such as a backboard early in resuscitation efforts. This decreases wasting of compressive force by compression of the soft hospital bed. While re-positioning the patient, interruptions of chest compressions should be minimized and care should be taken to avoid dislodging any lines or tubes [13].

Hand Position and PosturePlace the dominant hand over the center of the patient's chest [19]. This position corresponds to the lower half of the sternum. The heel of the hand is positioned in the midline and aligned with the long axis of the sternum. This focuses the compressive force on the sternum and decreases the chance of rib fractures. Next, place the non-dominant hand on top of the first hand so that both hands are overlapped and parallel. The fingers should be elevated off the patient's ribs to minimize compressive force over the ribs. Also avoid compressive force over the xiphisternum or the upper abdomen to minimize iatrogenic injury.

The previously taught method of first identifying anatomical landmarks and then positioning the hands two centimeters above the xiphoid-sternal notch was found to prolong interruptions of chest compressions without an increase in accuracy [20]. Similarly, the use of the internipple line as a landmark for hand placement was found to be unreliable [21]. Therefore these techniques are no longer part of the international consensus guidelines [4,13,18].

For maximum mechanical advantage keep your arms straight and elbows fully extended. Position your shoulders vertically above the patient's sternum. If the compressive force is not perpendicular to the patient's sternum then the patient will roll and part of the compressive force will be lost.

Compression Rate and InterruptionsThe blood flow generated by chest compressions is a function of the number of chest compressions delivered per minute and the effectiveness of each chest compression. The number of compressions delivered per minute is clearly related to survival [22]. This depends on the rate of compressions and the duration of any interruptions. Chest compressions should be delivered at a rate of at least 100 compressions per minute [4] since chest compression rates below 80/min are associated with decreased ROSC [2]. Any interruptions of chest compressions should be minimized. Legitimate reasons to interrupt chest compressions include the delivery of non-invasive rescue breaths, the need to assess rhythm or ROSC, and defibrillation [18]. Hold compressions when non-invasive rescue breaths are delivered [18]. Once an advanced airway is established there is no need to hold compressions for further breaths. High-quality compressions must also continue while defibrillation pads are applied and the defibrillator is prepared [13]. Aim to minimize interruption of chest compressions during the changeover of rescuers. Including all interruptions the patient should receive at least 60 compressions per minute [13].

Compression Depth, Recoil and Duty CycleCompression depth should be at least 5 cm, since sternal depression of 5 cm and over results in a higher ROSC [18]. No upper limit for compression depth has been established in human studies but experts recommend that sternal depression should not exceed 6 cm [13].

After each compression, allow the chest to recoil completely. Incomplete recoil results in worse hemodynamics, including decreased cardiac perfusion, cerebral perfusion and cardiac output [23]. Complete recoil is achieved by releasing all pressure from the chest and not leaning on the chest during the relaxation phase of the chest compressions [13]. However, avoid lifting the hands off the patient's chest, since this was associated with a reduction in compression depth [24].

The duration of the compression phase as a proportion of the total cycle is termed duty cycle. Although duty cycles ranging between 20% and 50% can result in adequate cardiac and cerebral perfusion [25], a duty cycle of 50% is recommended because it is easy to achieve with practice [4]. Thus the duration of the compression phase should be equivalent to the duration of the decompression phase. If the patient has hemodynamic monitoring via an arterial line then compression rate, compression depth and recoil can be optimized for the individual patient on the basis of this data.

Rotating RescuersThe quality of chest compressions deteriorates over time due to fatigue [26]. Therefore the compressor should be rotated every two minutes [13]. Rotating compressors more frequently than this may have detrimental effects due to interruptions of chest compressions from the practicalities of the changeover [27]. Consider rotating compressors during any intervention associated with appropriate interruptions of chest compressions, for example when defibrillating. Every effort should be made to accomplish the switch in less than five seconds. For this purpose it may be helpful for the compressor performing chest compressions to count out loud [13]. If the rotating compressors can be positioned on either side of the patient, one compressor can be ready and waiting to relieve the working compressor in an instant [4].